Site Fidelity and Distributions of Wintering Mallards

Waterfowl Feeding in moist soil unit at WingSelect. In early December 2022, mallards made up the majority of ducks in this unit until a massive cold front began to push through the continent locking up large bodies of water at higher latitudes. As a result, ring-necked ducks (diving ducks) began to make up a larger proportion of ducks on this moist soil wetland.

Site Fidelity

Site Fidelity - “The tendency to return to previously visited locations” (University of Washington. UW News. 2022). How many of the mallards in this video are adult birds visiting the farm for their second year or more? How many of the mallards are hatch year birds here for their first winter? Did they follow the other adults birds to this field? What costs and benefits could come with the propensity to return to the same wintering locations? If birds show high site fidelity to wintering locations what does this mean for harvest and regulations? Could killing the returning birds have long-term effects on the local wintering population? What changes in habitat are we seeing that could change the winter distribution and site fidelity of mallards across North America?

Rethinking Mallard Migration

With more and more data from banding and telemetry research providing evidence of waterfowl demonstrating site fidelity on wintering grounds (wintering fidelity), maybe it’s time to re-examine how we understand mallard migrations. Instead of seeing the North American mallard population as one large group of birds that move in tandem from north to south across the landscape, maybe a more accurate portrayal would be numerous sub-groups venturing on various migration routes to previously visited winter home ranges. These wintering home range habitats lie up and down the flyways with clumped distributions across a broad spectrum of latitudes. The “clumps” or major concentrations most likely occurring in areas of quality wetland habitat with minimal hunting pressure and disturbance. In other words, there are sub-populations of birds that winter in different regions across the North American landscape, utilizing areas of quality habitat. From Canada, to Nebraska, to Arkansas these birds spread out well below the freeze and snow lines to utilize the best habitats they can locate.

Are birds short-stopping in the north and not flying further south with a warming climate? As for now, I'm not convinced… They’ve wintered in various lattitudes across the North American landscape searching for quality habitat for thousands of years. If there are changes in distributions of wintering mallards, it may be more tied to changes in habitat than mild winters (conversely, there are changes in habitats occurring as a result of a warming climate). If the entire North American Mallard population concentrated on habitats in a few degrees of higher latitude, this would potentially increase intraspecific competition for food resources. Therefore, it may be more advantageous for mallards to maximize their use of limited food sources/habitats by wintering in a broad range of latitudes.

Will hard weather push large groups of birds further south and will mild winters make habitats at higher latitudes more available? Absolutely, but if site fidelity holds true, a mallard who has spent several successful winters in Kansas will have a tendency to return to Kansas and a bird that has successfully wintered in Arkansas will return to Arkansas as photoperiods shorten.

Recent Telemetry Research

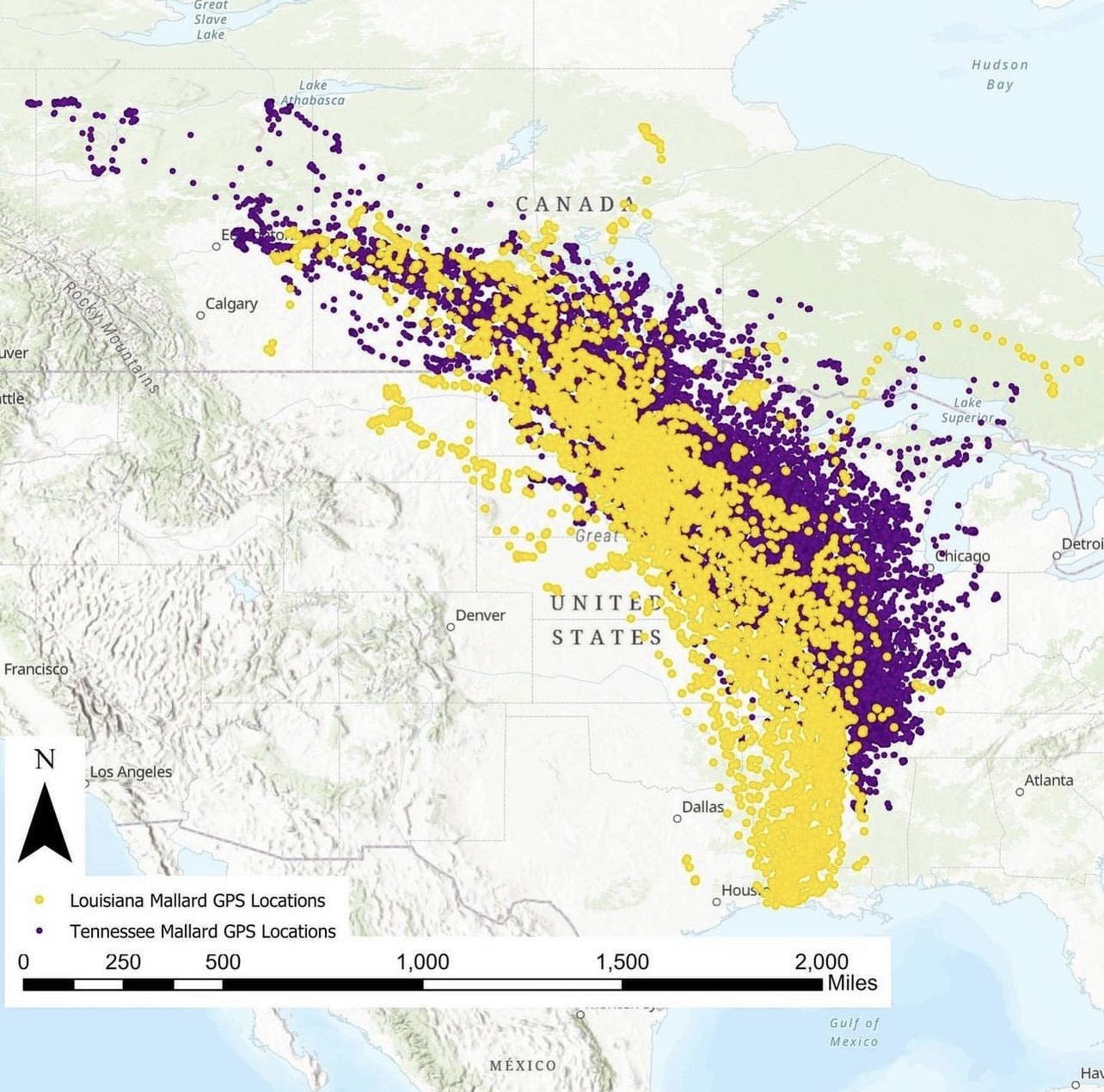

Recent telemetry data from Dr. Bradley Cohen’s Research Lab at the Tennessee Technological University was shared (map image below) showing GPS points from two different mallards exhibiting site fidelity. One bird was banded in the winter by Biologist Paul Link in Louisiana and the other bird was banded during the winter as well by Dr. Cohen’s team in Tennessee. In the map we can see that the yellow GPS points for the Louisiana Mallard make their way to latitudes in Louisiana, while the Tennessee bird with purple GPS points exhibited wintering fidelity for its winter captured location in west Tennessee.

Image: Dr. Bradley Cohen - Cohen Wildlife Research Lab

“Here is a map of GPS locations of mallards tagged by our collaborator Paul Link in Louisiana in Yellow added to our previous map of our west TN mallard locations. It fills out the Mississippi Flyway pretty well. Studies across North America are starting to paint an interesting picture. We are noticing relatively high winter site fidelity amongst waterfowl. So what we may have is groupings of mallards that go back to the same wintering area every year. Researchers, including us, are working on the bigger question about if duck migrations are shifting. But another possibility is that high-quality wetlands produce ducks with high winter site fidelity and shifts in harvest or migration are a byproduct. What we see in Tennessee is just one data point to a much larger question that all waterfowl biologists and researchers are trying to answer.” Dr. Bradley Cohen

Mallards utilizing a deep water oxbow lake at WingSelect during a hard freeze. At the WingSelect farm, we’ve observed that it’s hard to drive birds off of their winter home range with harsh weather events and they’ll typically move to deeper water during freezes and wait until the seed and grain fields become open.

Energetic Expenditures & Genetics?

When thinking about the energetic gains and expenses of migration, there could be some benefits to wintering fidelity… Seeking new wintering locations each season may have more energetic costs as opposed to returning to the same quality habitat area year after year. Returning to areas where the birds have memory of various landscape and habitat features would allow for faster access to food and cover sources. Searching for new areas of quality habitat every winter could potentially require more costly flight hours. On the other hand, seeking new habitats could also have the benefit of locating an area with better habitat, less hunting pressure, or an area completely absent of hunting. One possibility is that mallards show wintering fidelity to areas of quality-habitat and will only seek new wintering areas if habitat conditions decline. A ‘decline’ being something like increased hunting pressure or less waste grain in an agricultural field.

In addition, mallards may be genetically hard-wired to return to the same wintering locations. Birds that carry the genes for this behavior may have higher survival rates and henceforth higher reproduction rates. Therefore, there could be selection for these theoretical wintering fidelity genes.

This is all speculation beyond the fact that a significant portion of banded and transmitter mallards display wintering fidelity, but interesting to say the least and where the next frontier in understanding mallard migrations may begin. More research and larger sample sizes of tagged and banded mallards are needed to learn how likely it is that mallards will return to wintering locations and how the propensity to exhibit site fidelity is related to other factors such as climate and habitat quality.

A Changing Landscape and Shifting Flyways

Waterfowl distributions shifting as a result of changes in habitat have been documented with mid-continent greater white-fronted geese. White-fronted geese distributions shifted from the Gulf Coast of Texas and Louisiana to the north and east in the Mississippi Alluvial Valley (MAV) as the amount of rice acreage in the Gulf Coast decreased significantly (Moore et al., 2018). Former rice fields were converted to sugar cane and cotton production, primarily due to drought and water rights issues in the region. Geese shifted their primary wintering grounds to the MAV to utilize the growing amount of rice fields in the region (Moore et al., 2018).

Another important factor to consider is what kinds of competitive effects for food resources these early arriving light and white-fronted geese in the MAV have on later arriving wintering waterfowl like mallards. At the bottom of the page in the section ‘Citations & Links’ is a study by R. J. Askren and colleagues that dives into the timing of migration and habitat selection by greater white-fronted geese. Askren and colleagues examine how interspecific competition for shared food resources between dabbling ducks and early-arriving geese in the MAV may be underestimated in current bioenergetics models.

Mallards may be exhibiting similar distributional shifts in the MS flyway as changes in habitat across the landscape concentrate birds on areas of quality habitat and shift them away from areas of decreasing habitat quality. As of now, there is no evidence of mallard distributions shifting. Below, is a map generated by The Osborne Lab that shows the band encounter/harvest distributions of mallards that were winter banded in Arkansas. The mallard harvest distribution maps are broken down into three different time periods from 1950 to 2017.

My interpretation of the maps is that mallards that were banded during the winter in Arkansas display wintering fidelity for Arkansas. Arkansas winter banded mallards have had the highest density of harvest/encounters in Arkansas for nearly 70 years. Plain and simple, mallards that are banded during the winter in Arkansas come back the following winter(s).

“Have mallard distributions shifted?…No evidence for it, at least not at the landscape scale. You may notice slight changes in local distributions and many factors can impact annual differences. The map demonstrates winter harvest distribution of mallards banded during winter in Arkansas over 3 different time periods. How do you interpret these maps?” The Osborne Lab - University of Arkansas at Monticello

Farming Efficiencies And Habitat Quality in Arkansas

Over the years, agricultural fields in the MAV continue to have less waste grain (spillage) after harvest as combine efficiencies improve. In addition to increased combine efficiencies, the practice of fall tillage has become fairly common in Arkansas rice fields. This practice obscures much of the grain from waterfowl leaving very little food for migrating birds. With this in mind, one could speculate that one significant reason why some Arkansas hunters “aren’t seeing the birds they used to” is the overall decrease in flooded agricultural grain on the landscape.

In the early days of rice farming in Arkansas, fields were harvested with old inefficient farming methods leaving large amounts of waste rice in the fields (Warriner et al., 2013). With minimal weed control, wild millets, sprangletop, and other native moist soil plants were probably extremely abundant in these fields, further increasing the amount of available forage for waterfowl. The early-20th century is when Arkansans described scenes of mallards that blacked out the sky in the Grand Prairie (Warriner et al., 2013). Why were there so many ducks that it blacked out the sky? An abundance of food in the form of rice grain.

To help combat the decreasing amount of waste grain in Arkansas, The Waterfowl Rice Incentive Conservation Enhancement program (WRICE) was created by Arkansas Game & Fish Commission biologists. The program provides additional income for farmers to refrain from fall tillage and flood their fields for waterfowl. This is one small step, but an important one in our conservation journey as stewards of wintering mallards in Arkansas.

Habitat, Hunting Pressure/Disturbance, & Harvest

It seems safe to assume that migratory waterfowl follow the food and return to areas where they have a good chance at survival, and that’s what we can see here at WingSelect. Mallards return each winter like clockwork, demonstrating similar phenology over the past several winters. The first three weeks of November, as photoperiods approach the shortest length, is when we typically pick up large groups of mallards year after year. The ducks at WingSelect don’t have transmitters, but if they did, I’d be willing to place a bet that a large percentage of the adult birds are returning migrants. If these birds are returning migrants to the farm, what implications are there for harvesting breeding pairs wintering on the farm? If a significant portion of the local wintering breeding pairs are killed, what does that mean for the returning population the following winter? Will this decrease the local wintering population?

As far as regulations go for Arkansas and all flyways, It’s probably best to err on the conservative side of regulations. What if we are over-harvesting breeding pairs and therefore decreasing the returning wintering population of mallards? We may not currently have the concrete data to prove that notion, but we very well could be over-harvesting local wintering populations. Better to reduce season days and bag limits now than to take action after more data comes in supporting this notion. What’s wrong with fewer dead ducks? And as Brent Birch, editor of Greenhead Magazine, said, “dead ducks don’t lay eggs.”

Managing waterfowl sustainably ultimately comes down to three key factors: habitat, hunting pressure/disturbance, and harvest. If we can manage those factors, we will be successful in sustaining and increasing wintering waterfowl populations in The Natural State.

Citations & Links

Dead Ducks Don't Lay Eggs - Brent Birch

The Grand Prairie - Past Present Future - The Arkansas Natural Heritage Commission

Warriner, M., Witsell, T., Jones-Shulz, J., Krystofik, J., & Foti, T. (2013). The Grand Prairie of Arkansas - Past Present Future. https://www.arkansasheritage.com/docs/default-source/anhc-educational-resources/grand-prairie-of-arkansas-2nd-ed.pdf?sfvrsn=3f130099_6. Retrieved December 26, 2022, from https://www.arkansasheritage.com/docs/default-source/anhc-educational-resources/grand-prairie-of-arkansas-2nd-ed.pdf

Understanding Waterfowl - Tracking the White-Fronted Goose Migration

Moore, C. B., Askren, R. J., Osborne, D. C., & James, J. D. (2018, November). Understanding waterfowl: Tracking the white-fronted goose migration. Understanding Waterfowl: Tracking the White-Fronted Goose Migration - The distribution of midcontinent white-fronted geese has shifted in response to changing agricultural practices on the birds' wintering grounds. Retrieved December 26, 2022, from https://www.ducks.org/conservation/waterfowl-research-science/understanding-waterfowl-tracking-the-white-fronted-goose-migration